Strange but somehow Beautifull

Art of the Adan People of south-east Ghana

By Michael Yates

and the right arm pointing downwards are "calling on God". [1]

Early accounts of Adan Art

Types of Adan figurative Art

"Le monde invisible est le maitre du visible" Guérin Montilus [4]

Occasionally, one finds such figures using both arms to hold the container on the head.

The chief difference here is that Asisiagbate carries a "load", symbolizing commerce, rather than water. Things, however, can be further complicated when one sees that some "water carrier/load carrying" figures are also carved with missing limbs. There is also a third type of Adan figurative carvings, namely of "normal" looking people carved with two arms and two legs. According to de Surgy they are called Avlé and are "for the hearts of the victims of magic practices or the traps of the bush".

Notes:

- Robert Ferris Thompson Aesthetic of the Cool. Afro-Atlantic Art and Music Periscope Publishing Ltd., Pittsburg & New York. 2011. p. 43.

- The quotation can be found in Maya Deren's excellent study of Voodoo, Divine Horsemen. The Living Gods of Haiti 1953. p. xiv.

- For a rare 1950's recording of a group of Adan singers, see the Ohue Sapey Band performing Oblemo on the four CD set Opika pende - Africa at 78rpm Dust to Digital DTD22. Atlanta, 2011. C02, track 15.

- Guérin Montilus "L'homme dans la pensée traditionelle Fon" 1979. Cotonou. Mimeograph. Quoted in Suzanne Preston Blier African Vodun. Art, Psychology, and Power The University of Chicago Press. Chicago and London, 1995. p. 171.

- Suzanne Preston Blier African Vodun. Art, Psychology, and Power The University of Chicago Press. Chicago and London, 1995. p. 83.

- Roberto Pazzi "L'Homme eve, aja, gen, fon et son univers: Dictionnaire." Lome, Togo. 1976. Mimeograph. Quoted In Suzanne Preston Blier African Vodun. Art, Psychology, and Power The University of Chicago Press. Chicago and London, 1995. p. 83.

- I am using the spelling Ewe for these people. Both De Surgy and Blier use Evhe, which is closer to the correct pronunciation.

- The object was being sold by the American art dealer J. K. Rasmussen of the Dark Shrine Gallery in Washington.

- I found these comments on the webpage of a tribal art dealer. The page seems to have now removed from the web.

- See, for example, Allen F. Roberts Animals in African Art The Museum for African Art, New York, & Prestel, Munich. 1995.

- Robert Goldwater Senufo Sculpture from West Africa The Museum of Primitive Art New York. 1964. p. 28.

- Various authors Geest en Kracht — Vodun uit West-Afrika / Spirit Power — West African Vodun The Afrika museum, Bergen Dal, The Netherlands. 1996. p.113. (Dutch and English text).

- For a comparison with Ashanti stools, see the set of illustrations in Sandro Bocola (ed) African Seats Prestel, Munich & New York. 1995. pp. 44-45.

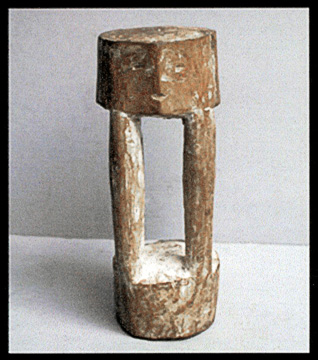

- Although described to me as "spirit houses" by the English person who sold them to me, I have to say that I have never come across similarly described objects elsewhere in African. However, there is a very similarly shaped image of a stool, 27.2 cms in height, shown in Sandro Bocola (ed) African Seats Prestel, Munich & New York. 1995. pp. 56 & 170. The original is in the collection of The Africa Museum, Tervuren, Belgium.